“Be still and know that I am. Be still and know. Be still. Be.”

—St. Patrick

These meditative words of St. Patrick seem appropriate in my quest to trace my Irish-American bloodline, as my father had desired to be laid to rest next to his beloved grandmother (provider of these Irish roots) in Fostoria, Ohio, instead of next to his wife of 55 years. And so, the story branches back in time with this final wish of John ‘to be’ connected in eternal spirit with Anna Belle (the photos above are John c. 1950 and Anna Belle c. 1900), whose Irish 3rd great-grandfather sowed seeds in British America that became rooted two generations before the Revolution.

The lives of our ancestors are more fully understood when the history of their times expands their stories. This is even more important when going farther back in time when records might be missing, and questions regarding their being become harder to answer.

This ancestral history begins with the Irish family name Kelley (Irish Gaelic: O Ceallaigh), which has an ancient origin meaning ‘warrior’ (war or contention) that goes back to Ceallach, the celebrated 9th century chieftain who led the sept, or Irish clan. Kelley translates as a descendent of Ceallach and also means ‘bright-headed’ (keen, confident, and alert). This was the maiden name of Anna Belle’s mother, Minerva (Kelley) German (1838-1916).

Minerva’s father, Thomas Kelley (1800-1887), had established the family in Northwest Ohio in 1831, when they moved to Washington Township (which he had the honor of naming) in Hancock County (Fostoria, Ohio, would be founded in 1854, and spread into Hancock, Seneca and Wood Counties). Thomas had made his first move west in 1811 with his father, Charles (1754-1847) and their family into the Connecticut Western Reserve, settling on a farm four miles from Wooster, Ohio. Charles, his wife Jemima (Crownover), and their first son Ezekiel had made their first move west prior to the first U.S. Census in 1790, when they settled among the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. They had lived in the Garrison Forest in Owings Mills, Maryland, where the first Kelleys would settle in the 1730s.

In 1707, James Kelley II (my 5th great-grandfather) was born in Macroom, County Cork, Ireland; according to family history on Ancestry.com, James came to the American Colonies in 1733. He was on a ship originally destined for the port of New York, but due to a violent storm off the coast of New England, the ship diverted to the port of Baltimore in the British Colony of Maryland. No records have been found of ship manifests that verify his arrival in 1733. Baltimore County Families, 1659-1759, authored by Robert William Barnes, lists James Kelly as being “in Baltimore County by 1737.” He would marry Prudence Logsdon in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Md., on Sept. 2, 1735.

Another source, FamilySearch.com, suggests the possibility that James may have been born in the colonies, which if correct means that his father, James, was the first Kelley to land in British Colonial America: “When “James Kelley I was born in 1687, in Kinneigh, County Cork, Ireland, his father, Joseph Patrick Kelley, was 29 and his mother, Ellen Mary McSwinney, was 25. He married Mary Elizabeth Dye in about 1704, in British Colonial America (meaning James II, born in 1707, could have been born in America and not Ireland unless Mary Elizabeth had made her way back to Ireland by that year). James and Mary Elizabeth were the parents of at least 6 sons. He died in 1750, in Baltimore, Maryland, British Colonial America, at the age of 63.” James Kelley II would settle in the Garrison Forest of Owings Mills, about 20 miles northwest of Baltimore, where he would die in 1779 during the American Revolution.

The opportune lure of a new beginning, plentiful land, and religious tolerance may have all been reasons the Kelley branch of my lineage came to British America. It is not known what religion the Kelley family professed in Ireland; it is known that James Kelley II would exchange Episcopalian marriage vows in colonial British America. The history of Ireland before they landed in America was one of conflict, inequality, and intolerance. England was establishing control in ways that were perilously absurd to the majority of Irish peasants. Irish colonizers arrived from England and Scotland who were Protestant, seeking fertile land, and an important strategic imperative to protect the Irish nation, and thus England, from the encroaching Roman Catholic countries France and Spain. They saw the Irish population as being a mongrel breed of Catholic peasants who were brutish and uncivilized. A Protestant Ascendancy began in the 1690s, and the English elite benefited as property rights of Catholics were trampled. Aristocratic gains were fostered by commemorating severe Protestant losses suffered during the Irish Rebellion of 1641, in which a Catholic uprising attempted to end discrimination, gain more self-governance, and get back their lands which had been turned into plantations by earlier English colonizers.

“It is not possible at present to provide a definitive account of the various factors and influences that combined to constitute Protestant identity in early modern Ireland, but the impact of their historical experiences in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and their commitment to the British monarchy were key features, which were cultivated and sustained by commemoration throughout the period 1660-1800,” wrote James Kelly in his article “‘The Glorious and Immortal Memory’: Commemoration and Protestant Identity in Ireland 1660-1800”. Kelly continues: “The bulk of those who constituted the ‘Protestant interest’ in late early modern Ireland were the descendants of settlers who arrived in the kingdom between 1550 and 1660. As a consequence, they were products of the defiantly Protestant identity forged in Britain in the sixteenth century, when the dominant issue in European history was religious conflict, and Catholics and Protestants locked horns in a struggle for ideological and dynastic supremacy.”

The Kelley family history and their property rights in Macroom, County Cork, Munster Province remain a mystery. As James Kelley II was married in St. Paul’s Parish in Baltimore County, he likely was one of the Protestant settlers in Maryland who soon were to be a majority in a Catholic proprietorship. His family in Ireland may have been dissenting Protestants (Presbyterians), who refused to accept the Anglican Church of England and the monarchy of Charles I. “Presbyterians who arrived from Scotland after 1600 comprised the bulk of Dissenters whereas smaller groups who owed their origin largely to the arrival of Cromwellian forces stagnated or declined after 1700,” according to Andrew Holmes in The Oxford History of Protestant Dissenting Traditions, Volume II: The Long Eighteenth Century c. 1689-c. 1828. The Kelley’s could also have been Royalists fighting the English Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Or, least likely, they could have been Roman Catholics. “Dissenters were part of a protestant minority in predominantly Catholic Ireland, yet Presbyterians were excluded from full participation in public life by the Church of Ireland ruling elite (the Church of England and the Church of Ireland would eventually be united by The Act of Union in 1800). This fueled political dissent that was, in turn, informed by New Light Presbyterianism that rejected subscription to theological formularies…” Holmes continues.

The English Civil War (1642-1651) through the Seven Years War (1756-1763) played havoc with Marylander’s liberty of conscience. The 17th Century conflict affected England, Ireland, Scotland, and British America as Royalists attempting to preserve the monarchial monopoly of Charles I to tax and wage war as an absolutist right were fighting Parliamentarians seeking more sovereign rights for the people. It was a time of antithetical ideas as multitudinous pamphleteers wrote about reason, the nature of man, and the evangelical teachings of the Bible. As seen by Protestant and Puritan subjects, Anglican Bishops served the interests of the king and the Church of England, while Jesus and his teachings served the interests of his followers. “That the English wrapped up every idea and attitude in religious language and used precedents from Scripture as their best authority gives the period the aura of a struggle about obsolete causes. But these causes were double, and the ideas hidden by the pious language were, as is foolishly said, ‘ahead of their time,’ meaning pregnant for the future. The sects and leaders classed as Puritans, Presbyterians, and Independents, were social and political reformers. They differed mainly in the degree of their radicalism,” wrote Jacques Barzun in From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life. Many Englanders, Scots, and British Americans saw the Church of England and its Anglican gentry as little different from the Roman Catholic Church; the church Henry VIII broke with because of the Pope’s refusal to grant him a divorce.

In England during the 17th Century, wealth was being spread more equally among the gentry, yeoman, and the expanding merchant class. Agriculture was being transformed. Since medieval times it had been a feudalistic and intermediary means for the many who lived in the countryside and depended on their noble landlords for their way of life. A growing urban population, especially in London, compelled country landlords to enclose their properties to allow for pasture farming, which led to the Midland Revolt. Rising food and land prices allowed those who were profiting to buy more consumer goods. Children of the gentry and yeoman classes could now afford to attend Oxford or Cambridge, and if one wanted to enter the legal world the Inns of Court were “in fact more socially prestigious than the universities.” Upward mobility led this new generation of English citizenry to believe that they held more of a stake in the realm of finance, politics, and property rights. “Perhaps naturally, many members of the gentry and middling sort were drawn to Calvinism, taking their growing wealth as evidence of their predestined salvation. Not all Puritans were middling folk, nor were all middling folk Puritans — far from it — but their worldviews had many points of similarity. Many believed, quite naturally, that God favored the saved with success in this life. Health and wealth were therefore easy to take as signs of one’s own salvation,” wrote Jonathan Healey in The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England 1603-1689.

The absolutist posture of the Stuart Royalists was being questioned by the common folk and their Parlimentarian representatives in the House of Commons, and thus England’s elite began debating the social position of this new model of polity. “The growing wealth of those in society’s middle attracted comments, mostly negative, from their social superiors. The Earl of Northhampton, for one, worried about the proliferation of schools aimed at those outside the traditional elite: there was nothing, he said, ‘so hurtful to the commonwealth as the multitude of free schools’, which turned people away from soldiery and apprenticeships and instead led them to ‘go up and down breeding new opinions,'” wrote Healey.

Democratic thought among the masses was evolving in England, which was a threat to the more privileged. A growing middle class that sought a better education and a better life meant that the landed aristocracy, represented by The House of Lords, would lose political power. The House of Commons would be more than just freemen, who “had to own a minimum amount of property” to be considered such, and thus be “given a voice in Parliament to legitimize the rule of the king” — the Commons would bring forth the voice of the rabble who were fighting to rise up. As Jane Calvert and Anthony Lake write in their article, “From Necessity, Not Choice: Lessons in Democracy from Maryland’s Past”, “in such a highly stratified society, the masses of people were poor, uneducated, and politically ignorant. The ordinary working man was excluded from the political process. He was a political non-entity, in bondage to a life of hard labor and dependence on his social betters, there to be ruled, not to rule themselves. Consequently, democracy — the rule of the common man — was unthinkable. It was considered the rule of the rabble, the rule of a class with neither the knowledge nor the ability to make political decisions. In other words, democracy was considered little better than anarchy.”

In the New World across the Atlantic, religious toleration formed the first democratic spirit of those Old World souls seeking its shores. The Roman Catholic Calvert family led by the Lords Baltimore founded the proprietary colony of Maryland in 1634 establishing a policy based on liberty of conscience that tolerated the practice of many Christian religions including Catholicism.

Maryland was named after Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I, and daughter of King Henry IV of France. “The title Baron of Baltimore in the Kingdom of Ireland was created in 1625, and conferred by James I (King of England and Ireland) on George Calvert, the first Baron. This was seven years before the grant of the Maryland Charter, and some years before the arrival hither of the first colonists. The title became extinct in 1771, upon the death of Frederick, the sixth Baron, five years before the declaration of the independence of the United States. It was in existence therefore for a little less than one hundred and fifty years, and its duration was nearly coincident with that of the colonial period of this commonwealth,” stated Clayton Colman Hall in his lectures “The Lords Baltimore and the Maryland Palatinate” at The John Hopkins University in 1902.

The Lords Baltimore “deliberately tried to create a society different from England’s, a society where religion was a private matter… This was a matter of both principle and necessity: the Calverts wanted their colony to be a refuge for fellow Catholics, but they also needed to attract as many settlers as possible if Maryland was going to be a success. The Calverts could afford to alienate neither prospective Protestant settlers nor the English government by favoring the Catholic Church. In any case, their own experience with religious discrimination led the proprietary family to support the principle of liberty of conscience,” wrote Beatriz Betancourt Hardy in her article “Roman Catholics, Not Papists: Catholic Identity in Maryland, 1689-1776” for Maryland Historical Magazine.

From the Province of Maryland’s founding in 1634 (and also in Virginia), proprietary and political partisanship was a means for survival in this new frontier in which “colonists cultivated tobacco for the English market and corn for themselves. The profits of tobacco attracted thousands of immigrants who dispossessed and killed natives and then cleared the forests to make hundreds of new farms and plantations,” wrote historian Alan Taylor in American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. “Maryland’s status as a safe haven played an instrumental role in the early forced immigration of the Irish to the colonies. In the 17th century, many Irish brought to the colonies were either indentured servants or prisoners-of-war from Oliver Cromwell’s conquering of Ireland. Because they were typically Catholic, the more tolerant Chesapeake colonies were often their initial destination,” according to PreservationMaryland.org.

“Lord Baltimore’s Palatinate of Maryland, with its first settlement … should have attracted an influx of Irish immigrants because of the Irish associations of the Calverts as English planters in County Longford and because of the religious toleration for Christians which prevailed in the colony until the Revolution of 1689, save for a few years during brief Puritan supremacy. However, comparatively few Irish men came to Maryland in the early period because of vague hopes of a happier future in Ireland under the Stuarts and because English manorial lords in Maryland seemed to prefer English laborers and indentured servants to Irish servants, despite the Protestantism or the Puritanism of the former. Apparently, nationalism was a more important factor than creed with the English Catholics in Maryland, who realized after all that they were ever on the defensive,” wrote Richard J. Purcell, PH.D., in his article “Irish Colonists in Colonial Maryland” for An Irish Quarterly Review.

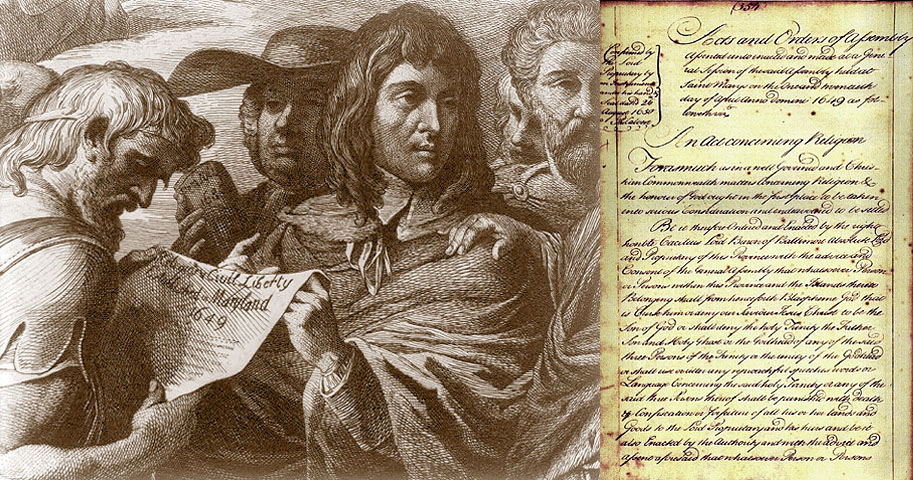

Along the Chesapeake Bay, the changes that were occurring in England led to a period known as “The Plundering Time,” (also known as Claiborne and Ingle’s Rebellion), which almost put an end to the Province of Maryland‘s future because of disputes over land, and political and religious partisanship. Choosing sides disturbed either the liberalism of Protestant settlers who felt politically threatened by an orderly Roman Catholic minority, who just wanted freedom of worship; or the peace of mind of Catholic settlers who felt alienated and threatened in their colonial refuge that for close to 125 years seemed to hold “greater appeal for Protestant dissenters, such as Quakers and Puritans who disagreed with the Church of England … Maryland’s real problem was figuring out how its religiously diverse people, a mix of England’s religious outsiders and members of the Church of England, could live with each other in harmony and order,” wrote Thomas Kidd in his article “The Founding of Maryland” for the Bill of Rights Institute. After the Parliamentary privateers led by Claiborne and Ingles were put down by colonial forces led by Maryland Governor Lord Baltimore in 1647, freedom of conscience was codified by the Colonial Assembly of Maryland in 1649 as “A Law of Maryland Concerning Religion”, which became known as the Maryland Toleration Act. The law stated that “…no person or persons … professing to believe in Jesus Christ, shall from henceforth be anyways troubled, Molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof within this Province…”

“Between 1649 and 1660, England had no king, and became a commonwealth, and people took seriously the idea of a commonwealth, everyone in the same boat as everyone else, and it also got a little easier to pretend that there existed such a thing as the people, and that they were the sovereign rulers of … themselves. In England, new sects thrived, from Baptists to Quakers. The Diggers advocated communal ownership of land. The Levellers argued for political equality. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ocean, the colonies grew, and the colonists came to see themselves as the people, too. Not to mention, much of British America was itself the product of religious and political rebellion, each colony its own experiment in the rule of the people and freedom of speech,” wrote Jill Lepore in her excellent history of the United States, These Truths.

Sectarianism was also rampant in Macroom and County Cork as Kelley’s ancestors were caught up in the Eleven Years War (1641-1653) between an Irish Catholic Confederation and a Cromwellian English Parliamentarian force, who were soon to conquer Ireland. Wars were being waged by the English Commonwealth in three kingdoms: England, Ireland, and Scotland. Ireland suffered horrific casualties — “618,000 deaths from fighting and disease out of a total pre-war population of c. 1.5 million, or 41 percent of the population … Cromwell and his supporters considered Irish Roman Catholics as little better than savages, barbarian in their lifestyle and habits, and capable of appalling atrocities against Protestant settlers. They were sub-human and dangerous, and were to be treated accordingly,” wrote Noel M. Griffin in his article “How many died during Cromwell’s campaign?” for History Ireland.

Three years after the Battle of Macroom (May 10, 1650) in which several hundred Irish Confederates were killed during a cavalry charge, the Commonwealth granted Macroom Castle to Admiral William Penn, the father of Pennsylvania’s founding father, William Penn. Young William lived there from 1656-1660, and it was within these walls that his religious mindset was converted. “A traveling Quaker preacher, Thomas Loe, was invited by Admiral Penn to address his household in Macroom in 1657, and both Penn senior and junior appear to have been deeply impressed by him.” 25 years later Penn wrote his Frame of Government for Pennsylvania. In the preface, Penn writes, “Government seems to me a part of religion itself, a thing sacred in its institution and end…And government is free to the people under it, whatever be the frame, where the laws rule and the people are a party to those laws; and more than this is tyranny, oligarchy, or confusion…As governments are made and moved by men, so by them, they are ruined too. Wherefore governments rather depend upon men than men upon governments. Let men be good, and the government cannot be bad. If it be ill, they will cure it. But if men be bad, let the government be ever so good, they will endeavor to warp and spoil it to their turn.”

How the Cromwellian conquest may have affected the Kelley family in County Cork can only be seen in the context of the catastrophic casualties that the Irish people encountered. Ancestry records have established that Joseph Patrick Kelley, was born in Macroom in 1658, but before Joseph Patrick, the lineage is uncertain. Èol Kelley (born c. 1638) may have been Joseph Patrick’s father according to a singular source, Mara Toby Horowitz, MD. An interesting name, Èol is the poetic form of Aeolus (Αἴολος) in a sense “moving, swift, to turn”, in Greek mythology he is the god of the winds. The Irish Confederate Wars between 1641 and 1653 were definitely a tempest and much would need to be restored.

Back in the New World, the Battle of Severn may have been the “last battle of the English Civil War,” suggested author Radmila May in her article “The Battle of Great Severn.” It was fought in the settlement of Providence (Annapolis since 1694) on March 25, 1655, when Puritans, who were supporters of the Commonwealth of England, defeated the Catholic and Royalist men, led by the religiously tolerant Protestant governor, William Stone, who supported the lord proprietor, the 2nd Baron Baltimore, Cecil Calvert. Stone was imprisoned for several years and “the Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act.”

The Stuart Restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660 occurred because the English people were growing tired of the austere Cromwellian religious policies that were enforced by the army, according to English historian Godfrey Davis. Parliament offered to let Charles reign as successor to his beheaded father, Charles I if he would agree to tolerate freedom of worship and provide a general amnesty. “Constitutionally, it was as if the last nineteen years had never happened,” wrote historian Tim Harris.

In Ireland, a “massive scramble for land” was “characteristic of the Restoration Period, wrote Kevin McKenny in his article “Charles II’s Irish Cavaliers: the 1649 Officers and the Restoration Land Settlement” for Irish Historical Studies. “In November 1660 the newly restored king published a declaration for the settlement of Ireland. The substance of this document was that the ‘adventurers’ of the 1640s and the Cromwellian soldiers were to keep what they had got; the Irish Protestants who had actively supported the royalist cause (especially between 1648 and 1650) and who had not yet obtained compensation for this service were to receive their arrears in pay; Irish Catholics who had been deprived of their lands merely on the grounds of their religion were to be restored to what they had lost. From the clash of these interest groups came the molding forces behind what is known as the ‘Restoration settlement…’”

Nevertheless, whatever religious persuasion they were in Ireland, “the Americas were a more common destination for the Protestants rather than the Catholics, considering the expensive transatlantic voyage,” wrote Howell citing Robert E. Kennedy’s The Irish: Emigration, Marriage, and Fertility.

To be continued by Mark A. Shephard